The Sterling Brown Project

Stream the full project below. Album available on iTunes, Spotify, Bandcamp, Apple Music, YouTube Music, and other popular streaming services.

Called “the Poet Laureate of the Jim Crow South,” Sterling Brown’s blues and folk poems drop the reader into the untold, hidden stories of African-American life. Police and vigilante violence, cotton fields and tenements are all rendered in gripping narratives and poignant verse.

Permission to reprint and adapt the poems was granted by Mrs. Elizabeth Dennis and the Estate of Sterling A. Brown.

Marisa in Vogue, Hale Woodruff (1973)

Hale Woodruff (1900–1980) was a central figure in the world of Black art in the 20th Century. In the September 21, 1942, issue of Time, Woodruff stated, “We are interested in expressing the South as a field, as a territory, its peculiar run-down landscape, its social and economic problems; the Negro people.”

Learn more on Hale Woodruff at the end of this section of the site.

Slim in Atlanta

Slim Greer is Sterling Brown’s trickster character. He made his first appearance in Brown’s work in 1932. Eighty-three years later, in 2015, a headline appeared in the Los Angeles Times: “Group of black women kicked off Napa wine train after laughing too loud.”

Down in Atlanta,

De whitefolks got laws

For to keep all de niggers

From laughin' outdoors.

Hope to Gawd I may die

If I ain't speakin' truth

Make de niggers do deir laughin'

In a telefoam booth.

Slim Greer hit de town

An' de rebs got him told,

"Dontcha laugh on de street,

If you want to die old."

Den dey showed him de booth

An' a hundred shines

In front of it, waitin'

In double lines.

Slim thought his sides

Would bust in two,

Yelled, "Lookout, everybody,

I'm coming through!"

Pulled de other man out,

An' bust in de box,

An' laughed four hours

By de Georgia clocks.

Den he peeked through de door,

An' what did he see?

Three hundred niggers there

In misery.

Some holdin' deir sides,

Some holdin' deir jaws,

To keep from breakin'

De Georgia laws.

An' Slim gave a holler,

An' started again;

An' from three hundred throats

Come a moan of pain.

An' everytime Slim

Saw what was outside,

Got to whoopin' again

Till he nearly died.

An' while de poor critters

Was waitin' deir chance,

Slim laughed till dey sent

Fo' de ambulance.

De state paid de railroad

To take him away;

Den, things was as usual

In Atlanta, Gee A.

Slim in Atlanta by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Arrangement by Rough Magic

Emma Alabaster, upright bass & vocals

Cornelius Eady, vocals

Leo Ferguson, drums & percussion

Lisa Liu, keyboards

Robin Messing, vocals

Charlie Rauh, guitar

Recorded and mixed Jim Bertini

Arkansas Chant

The devil is a rider

In slouch hat and boots

Gun by his side

Bull whip in his hand.

The devil is a rider;

The rider is a devil

Riding his buck stallion

Over the land.

The poor-white and nigger sinners

Are low-down in the valley.

The rider is a devil

And there’s hell to pay.

The devil is a rider,

God may be the owner,

But he’s rich and forgetful,

And far away.

Arkansas Chant by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Arrangement by Rough Magic

Concetta Abbate, violin

Emma Alabaster, upright bass

Cornelius Eady, lead vocals

Leo Ferguson, drums, percussion. prepared piano

Robin Messing, vocals

Charlie Rauh, guitar

Recorded, mixed & produced by Leo Ferguson

Untitled, Bill Traylor

“Bill Traylor…was about twelve years a slave, from his birth, in Dallas County, Alabama, in 1853 or so, until Union cavalry swept through the cotton plantation where he was owned, in 1865. Sixty-four years later, in 1939, homeless on the streets of Montgomery, he became an extraordinary artist, making magnetically beautiful, dramatic, and utterly original drawings on found scraps of cardboard.

“Charles Shannon—a painter and the leader of New South, a progressive group of young white artists in Montgomery—noticed and befriended Traylor in 1939, providing him with money and materials and collecting most of the roughly twelve hundred works of his that survive. New South mounted a Traylor show in 1940. Nothing sold. The support ended amid the disruptions of wartime in 1942. All of Traylor’s subsequent art is lost. He died in 1949 in Montgomery, and was buried in a pauper’s grave. — Peter Schejeldahl, The New Yorker

Bill Traylor was survived by at least fifteen children and today his art is featured in the collections of the The Museum of Modern Art, the Smithsonian, and scores of other museums and private collections.

All Me II, Winfred Rembert (2002)

Winfred Rembert was born in 1945 in Georgia. Put to work at six years old, he had little early education beyond picking cotton and potatoes. After dropping out of school in 1951, he became involved in the Civil Rights movement. Fleeing a sit-in that was being raided by the police, he stole a car, and was arrested, sent to prison, and briefly escaped from prison before being re-arrested.

“[I was] shipped to a chain gang in Leesburg, Ga. I kept being sent to the sweat box, where you stay in a crouch all the time. You can’t sit or stand up. They can keep you for 14 days, max. I was in the sweat box 330-plus times in the seven years I was there.…I was able enough to endure and hoping one day I’d be free.

“I found some well-educated black men in prison, and they taught me to read and write. One guy, a trusty, was making leather things, and I watched how he did it and made some of my own. I looked through the bars at him working, and I thought I could do it because I’m artistic. (folkart.org)

I’ve been sharing my story, as an artist, for the last twenty-five years. My pictures are carved and painted on leather, using skills I learned in prison.

It was my wife Patsy’s idea for me to become an artist. She kept telling me, listen, you can do it, and she kept pushing me. There were times in my life when it seemed to me there was no future. Every day Patsy pushed me to be positive. She gave me hope. (winfredrembert.com)

Today, Winfred Rembert lives in New Haven, Connecticut, and lectures at Yale University. Learn more at winfredrembert.com

Southern Road

Swing dat hammer — hunh —

Steady, bo';

Swing dat hammer — hunh —

Steady, bo';

Ain't no rush, bebby,

Long ways to go.

Burner tore his — hunh —

Black heart away;

Burner tore his — hunh —

Black heart away;

Got me life, bebby,

An' a day.

Gal's on Fifth Street — hunh —

Son done gone;

Gal's on Fifth Street — hunh —

Son done gone;

Wife's in de ward, bebby,

Babe's not bo'n.

My ole man died — hunh —

Cussin' me;

My ole man died — hunh —

Cussin' me;

Ole lady rocks, bebby,

Huh misery.

Doubleshackled — hunh —

Guard behin';

Doubleshackled — hunh —

Guard behin';

Ball an' chain, bebby,

On my min'.

White man tells me — hunh —

Damn yo' soul;

White man tells me — hunh —

Damn yo' soul;

Got no need, bebby,

To be tole.

Chain gang nevah — hunh —

Let me go;

Chain gang nevah — hunh —

Let me go;

Po' los' boy, bebby,

Evahmo' . . .

Southern Road by Sterling A. Brown

Read by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

Mose

Mose is black and evil

And damns his luck

Driving Mister Schwartz’s

Big coal truck.

He’s got no gal,

He’s got no jack,

No fancy silk shirts

For his back.

But summer evenings,

Hard Luck Mose

Goes in for all

The fun he knows.

On the corner kerb

With a sad quartette

His tenor peals

Like a clarinet

O hit it Moses

Sing att thing

But Mose’s mind

Goes wandering —

And to the stars

Over the town

Floats, from a good man

Way, way down —

A soft song, filled

With a misery

Older than Mose

Will ever be.

Mose by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Arrangement by Rough Magic

Concetta Abbate, violin

Emma Alabaster, upright bass & vocals

Cornelius Eady, acoustic guitar, lead vocals

Leo Ferguson, drums

Robin Messing, vocals

Charlie Rauh, guitar

Recorded & mixed by Leo Ferguson

Jacobia Hotel, William H. Johnson (1930)

William Henry Johnson was born March 18, 1901, in Florence, South Carolina, to Henry Johnson and Alice Smoot. He attended the first public school in Florence, the all-black Wilson School on Athens Street. Johnson practiced drawing by copying the comic strips in the newspapers, and considered a career as a newspaper cartoonist.

He moved from Florence, South Carolina, to New York City at the age of 17. Working a variety of jobs, he saved enough money to pay for classes at the prestigious National Academy of Design and at the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, Massachusetts, paying for his tuition, food and lodging in Cape Cod by working as a general handyman at the school.

Johnson spent time in Europe and worked with the WPA during the Great Depression. While rendering the Jacobia Hotel (above) in South Carolina he was nearly arrested for standing in the street and painting.

In 1956, all of his paintings were almost destroyed because he could not afford the storage fees he owed. However the work — over 1000 paintings and drawings — was rescued and stored by a foundation, and eventually acquired by the Smithsonian. Johnson died in 1970.

William H. Johnson's work continues to tell the story of Black life in America — his painting, Moon Over Harlem, could easily be a scene of police violence in the era of Black Lives Matter.

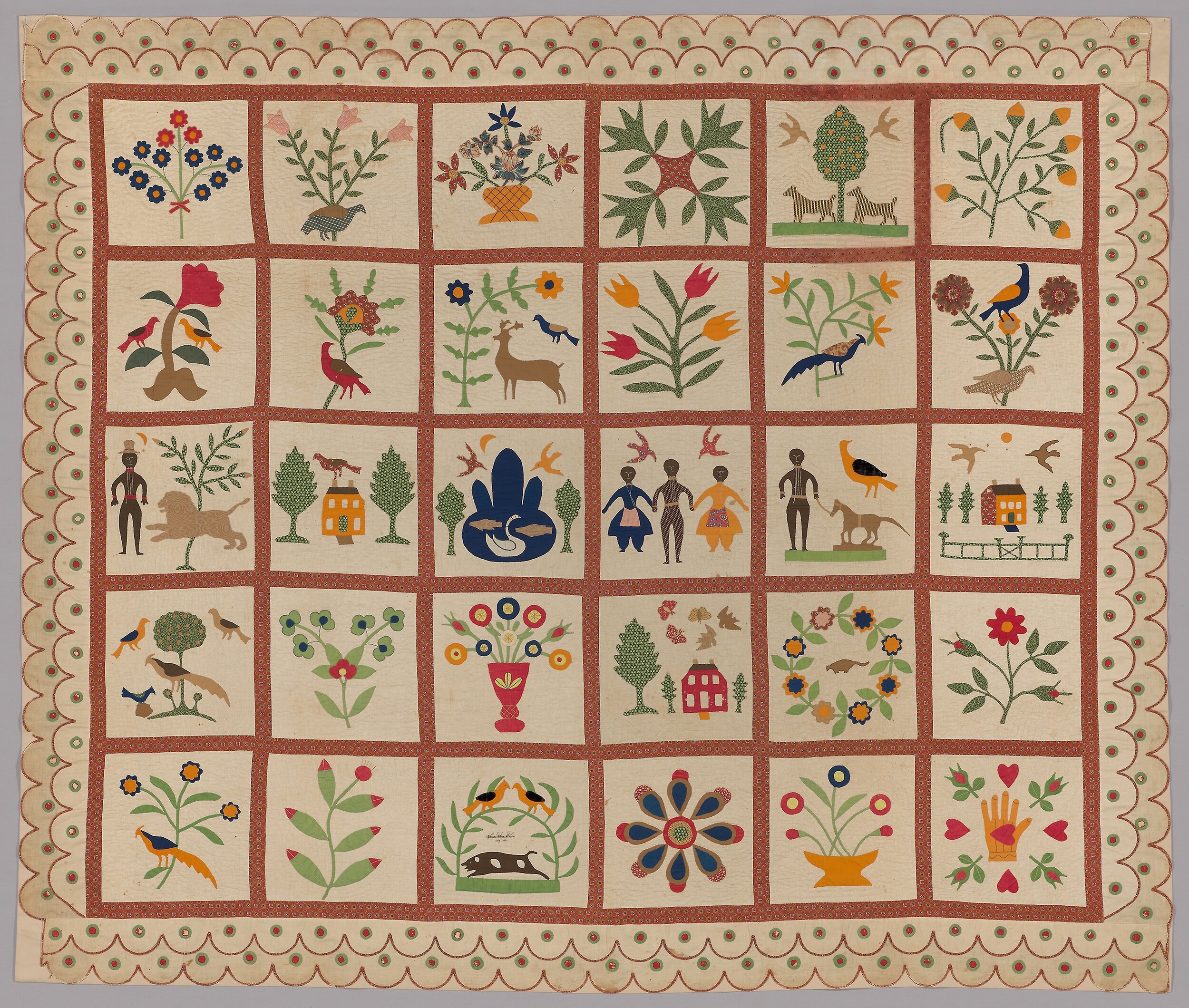

Quilt, Sarah Ann Wilson (1854)

Very little is known about the quilt’s maker, Sarah Ann Wilson, but she is believed to have been a free black woman living in New York, and the figures delicately appliquéd onto her quilt may represent her family members.

Maumee Ruth

Might as well bury her

And bury her deep,

Might as well put her

Where she can sleep.

Might as well lay her

Out in her shiny black;

And for the love of God

Not wish her back.

Maum Sal may miss her—

Maum Sal, she only —

With no one now to scoff,

Sal may be lonely....

Nobody else there is

Who will be caring

How rocky was the road

For her wayfaring

Nobody be heeding in

Cabin, or town

That she is lying here

In her best gown

Boy that she suckled —

How should he know,

Hiding in city holes,

Sniffling the ‘snow’?

And how should the news

Pierce Harlem’s din,

To reach her baby gal,

Sodden with gin?

To cut her withered heart

They cannot come again,

Preach her the lies about

Jordan, and then

Might as well drop her

Deep in the ground,

Might as well pray for her,

That she sleep sound…

Maumee Ruth by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Arrangement by Rough Magic

Concetta Abbate, violin

Emma Alabaster, upright bass

Cornelius Eady, acoustic guitar & vocals

Leo Ferguson, drums & percussion

Robin Messing, lead vocals

Charlie Rauh, guitar

Recorded and mixed by Leo Ferguson

Riverbank Blues

A man git his feet set in a sticky mudbank,

A man git dis yellow water in his blood,

No need for hopin', no need for doin',

Muddy streams keep him fixed for good.

Little Muddy, Big Muddy, Moreau and Osage,

Little Mary's, Big Mary's, Cedar Creek,

Flood deir muddy water roundabout a man's roots,

Keep him soaked and stranded and git him weak.

Lazy sun shinin' on a little cabin,

Lazy moon glistenin' over river trees;

Ole river whisperin', lappin' 'gainst de long roots:

"Plenty of rest and peace in these . . ."

Big mules, black loam, apple and peach trees,

But seems lak de river washes us down

Past de rich farms, away from de fat lands,

Dumps us in some ornery riverbank town.

Went down to the river, sot me down an' listened,

Heard de water talkin' quiet, quiet lak an' slow:

"Ain' no need fo' hurry, take yo' time, take yo' time . . ."

Heard it sayin' — "Baby, hyeahs de way life go . . ."

Dat is what it tole me as I watched it slowly rollin',

But somp'n way inside me rared up an' say,

"Better be movin' . . . better be travelin' . . .

Riverbank'll git you ef you stay . . ."

Towns are sinkin' deeper, deeper in de riverbank,

Takin' on de ways of deir sulky Ole Man—

Takin' on his creepy ways, takin' on his evil ways,

"Bes' git way, a long way . . . whiles you can.

“Man got his

sea too lak de Mississippi

Ain't got so long for a whole lot longer way,

Man better move some, better not git rooted

Muddy water fool you, ef you stay . . .

Riverbank Blues by Sterling A. Brown

Read by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

Baptism, Clementine Hunter (1955)

Clementine Hunter was a self-taught Black folk artist from the Cane River region of Louisiana, who lived and worked on Melrose Plantation. Born in late December 1886 or early January 1887 into a Louisiana Creole family at Hidden Hill Plantation near Cloutierville, in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, she started working as a farm laborer at an early age and never learned to read or write.

As a field hand and cook at Melrose Plantation, which was was both a working plantation farm and an artists' colony, Hunter started painting using supplies discarded by visiting artists. In her fifties, after the death of her husband, she began selling her paintings; on the outside of the cabin where she lived was a sign that read: "Clementine Hunter, Artist. 25 cents to Look."

Her early work depicted the South of her childhood, painted from memory. Later in life, when Parkinson's disease limited the precision of her hands, she developed a more impressionistic style.

Clementine Hunter was wildly creative throughout her life. She created murals, quilts and tapestries, and released a cookbook filled with the Creole recipes that she learned from her family and illustrated with her artwork; she created thousands of paintings, which, by the end of her life in 1988, sold for thousands of dollars.

An inspiration to multiple generations of Black artists and activists, she is also the subject of the opera Zinnias: the Life of Clementine Hunter, written by legendary musicians Toshi Reagon & Bernice Johnson Reagon, acclaimed author Jacqueline Woodson (and directed by Robert Wilson).

Pullman Porter’s uniform. Collection of the National Museum of African American History & Culture, circa 1889–1929. Photo illustration by Leo Ferguson (2021)

Long Track Blues

Went down to the yards

To see the signal lights come on;

Looked down the track

Where my lovin’ baby done gone.

Red light in my block,

Green light down the line;

Lawdy, let yo’ green light

Shine down on that babe o’ mine.

Heard a train callin’

Blowin’ long ways down the track;

Ain’t no train due here,

Baby, what can bring you back?

Brakeman tell me

Got a powerful ways to go;

He don’t know my feelin’s

Baby, when he talkin’ so.

Lanterns a-swingin’;

An’ a long freight leaves the yard;

Leaves me here, baby,

But my heart it rides de rod.

Sparks a flyin;

Wheels rumblin’ wid a might roar;

Then the red tail light

And the place gets dark once more.

Dog in the freight room

Howlin’ like he los’ his mind;

Might howl myself

If I was the howlin’ kind.

Norfolk and Western,

Baby, and the C. & O;

How come they treat

A hardluck feller so?

Red light in my block,

Green light down the line;

Lawdy, let yo’ green light

Shine down on that babe o’ mine.

Long Track Blues by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Arrangement by Rough Magic

Emma Alabaster, electric bass & vocals

Cornelius Eady, vocal

Leo Ferguson, drums, percussion, & keyboards

Lisa Liu, guitar

Robin Messing, lead vocals

Charlie Rauh, guitar

Chanell Crichlow, tuba

Bryan Walters, trumpet

T.J. Robinson, trombone

Brass arrangements by Leo Ferguson

Recorded, mixed & produced by Leo Ferguson

Southern Cop

Let us forgive Ty Kendricks.

The place was Darktown. He was young.

His nerves were jittery. The day was hot.

The Negro ran out of the alley.

And so he shot.

Let us understand Ty Kendricks.

The Negro must have been dangerous,

Because he ran;

And here was a rookie with a chance

To prove himself a man.

Let us condone Ty Kendricks

If we cannot decorate.

When he found what the Negro was running for,

It was too late;

And all we can say for the Negro is

It was unfortunate.

Let us pity Ty Kendricks.

He has been through enough,

Standing there, his big gun smoking,

Rabbit-scared, alone,

Having to hear the wenches wail

And the dying Negro moan.

Southern Cop by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Arrangement by Rough Magic

Emma Alabaster, electric bass

Cornelius Eady, lead vocal

Leo Ferguson, drums & keyboards

Robin Messing, vocals

Charlie Rauh, guitar

Recorded, mixed & produced by Leo Ferguson

Mural on the exterior of the Dairy Arts Center, in Boulder, depicting the late Sandra Bland. Spray Their Name artists Thomas “Detour” Evans, Hiero Veiga, Cya Jonae and Giovannie aka “Just,” (2020)

Haint (for Sandra Bland) by Cornelius Eady

I got this ache in my heart

The state of Texas is my host

I got this hole in my soul

The State of Texas made me a ghost

And my ghost howls

Woe

Now I’m a wandering spirit

My body swings in my cell

When they cut this poor gal down

Who’ll know how I got here?

And my ghost howls

Woe

Maybe I died by my own hand

Maybe I died by hands unknown

Maybe I was dead

The moment I talked back

Maybe I was dead

‘fore I was born

And my ghost howls

Woe

Damn the cop

Who damned my black skin

Damn the judge

Who agreed with him

My name’s Sandra Bland

I should be alive

Sass back in Texas

You commit “suicide”

And my ghost howls

Woe.

Untitled, Bill Traylor

Frankie & Johnny

Frankie was a half-wit, Johnny was a nigger,

Frankie liked to pain poor creatures as a little ‘un,

Kept a crazy love of torment when she got bigger,

Johnny had to slave it and never had much fun.

Frankie liked to pull wings off living butterflies,

Frankie liked to cut long angleworms in half,

Frankie liked to whip curs and listen to their drawn out cries,

Frankie liked to shy stones at the brindle calf.

Frankie took her pappy’s lunch week-days to the sawmill,

Her pappy, red-faced cracker, with a cracker’s thirst,

Beat her skinny body and reviled the hateful imbecile,

She screamed at every blow he struck, but tittered when

he curst.

Frankie had to cut through Johnny’s field of sugar corn

Used to wave at Johnny, who didn’t ‘pay no min’ –

Had had to work like fifty from the day that he was born,

And wan’t no cracker hussy gonna put his work behind.

But everyday Frankie swung along the cornfield lane,

And one day Johnny helped her partly through the wood,

Once he had dropped his plow lines, he dropped them many times again,

Though his mother didn’t know it, else she’d have whipped him good.

Frankie and Johnny were lovers, oh Lordy how they did love!

But one day Frankie’s pappy by a big log laid him low,

To find out what his crazy Frankie had been speaking of;

He found that what his gal had muttered was exactly so.

Frankie, she was spindly limbed with corn silk on her crazy head,

Johnny was a nigger, who never had much fun —

They swung up Johnny on a tree, and filled his swinging hide with lead,

And Frankie yowled hilariously when the thing was done.

Frankie & Johnny by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Arrangement by Rough Magic

Emma Alabaster, electric bass, vocals

Cornelius Eady, lead vocal

Leo Ferguson, drums & percussion

Robin Messing, vocals

Charlie Rauh, guitar

Recorded & mixed by Leo Ferguson

Sharecroppers

When they rode up at first dark and called his name,

He came out like a man from his little shack

He saw his landlord, and he saw the sheriff,

And some well-armed riff-raff in the pack. When they fired questions about the meeting,

He stood like a man gone deaf and dumb,

But when the leaders left their saddles,

He knew then that his time had come.

In the light of the lanterns the long cuts fell,

And his wife's weak moans and the children's wails

Mixed with the sobs he could not hold.

But he wouldn't tell, he would not tell.

The Union was his friend, and he was Union,

And there was nothing a man could say.

So they trussed him up with stout ploughlines,

Hitched up a mule, dragged him far away

Into the dark woods that tell no tales,

Where he kept his secrets as well as they.

He would not give away the place,

Nor who they were, neither white nor black,

Nor tell what his brothers were about.

They lashed him, and they clubbed his head;

One time he parted his bloody lips

Out of great pain and greater pride,

One time, to laugh in his landlord's face;

Then his landlord shot him in the side.

He toppled, and the blood gushed out.

But he didn't mumble ever a word,

And cursing, they left him there for dead.

He lay waiting quiet, until he heard

The growls and the mutters dwindle away;

"Didn't tell a single thing," he said,

Then to the dark woods and the moon

He gave up one secret before he died:

"We gonna clean out dis brushwood round here soon,

Plant de white-oak and de black-oak side by side.”

Sharecroppers by Sterling A. Brown

Read by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

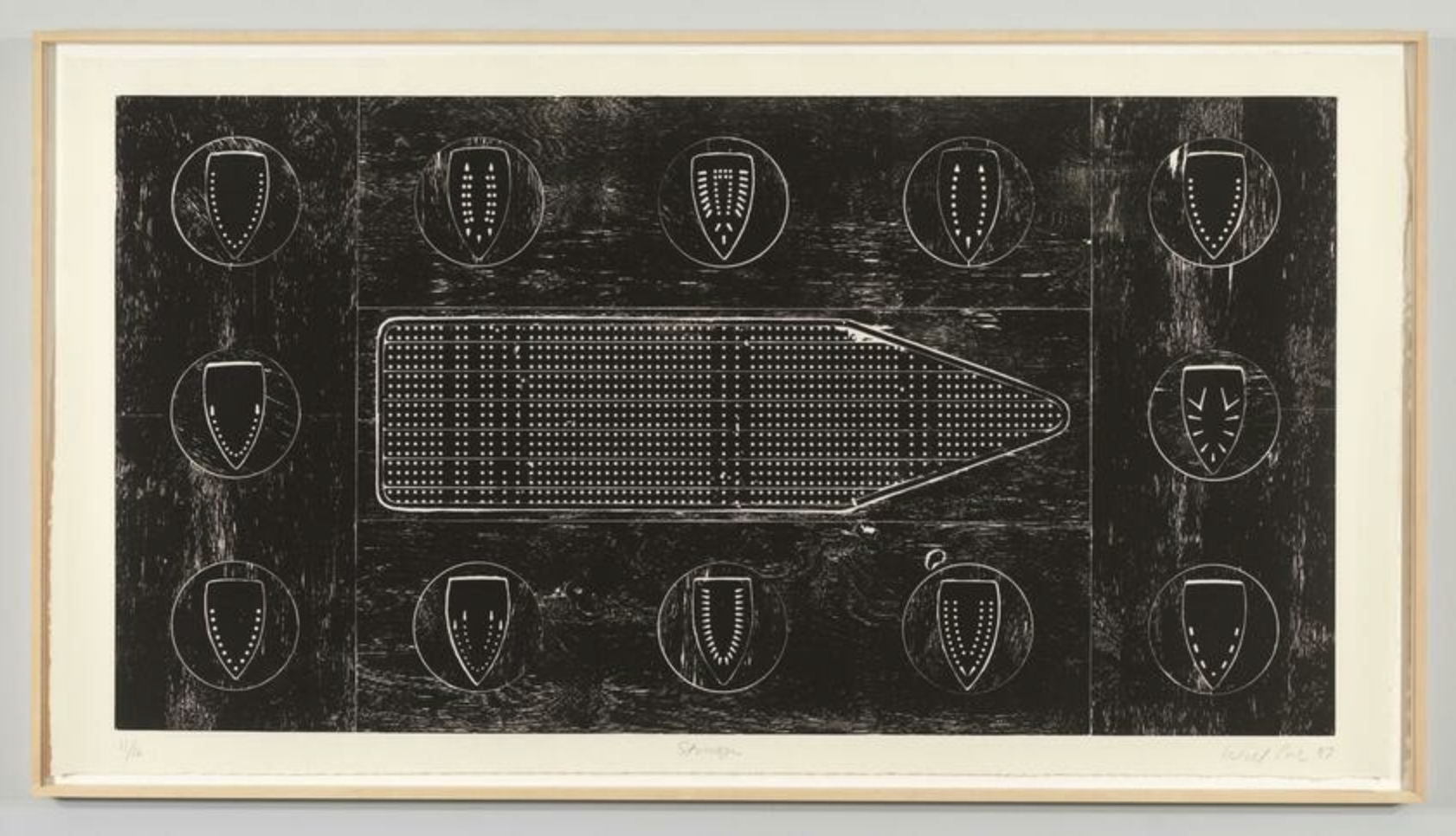

Stowage, Willie Cole (1997)

Hot Bodies, Willie Cole (2013)

Born in 1955, Willie Cole grew up in Newark, New Jersey. His upbringing by both his mother and grandmother in the 1960s has had a lasting impact on his work, as his continued use of irons in his sculptures signifies the domestic role of African women during this time.

He attended the Boston University School of Fine Arts, received his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the School of Visual Arts in New York in 1976, and continued his studies at the Art Students League of New York from 1976 to 1979. His fascination with African art developed as he continued his education at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where he studied the culture of the Yoruba society.

Cole is best known for assembling and transforming ordinary domestic and used objects such as irons, ironing boards, high-heeled shoes, hair dryers, bicycle parts, wooden matches, lawn jockeys, and other discarded appliances and hardware, into imaginative and powerful works of art and installations.

In 1989, Cole garnered attention in the art world with works using the steam iron as a motif. Cole imprinted iron scorch marks on a variety of media, showing not only their wide-ranging decorative potential but also to reference his Cole’s African-American heritage. He used the marks to suggest the transport and branding of slaves, the domestic role of black women, and ties to Ghanaian cloth design and Yoruba gods.

He lives and works in New Jersey.

According to Matthew Lessig,

"Sharecropper" was first published in 1939 in Get Organized: Stories and Poems about Trade Union People, one in a series of "literary pamphlets . . . written for members of trade union and other progressive organizations" put out by International Publishers, a New York publishing house affiliated with the Communist Party.

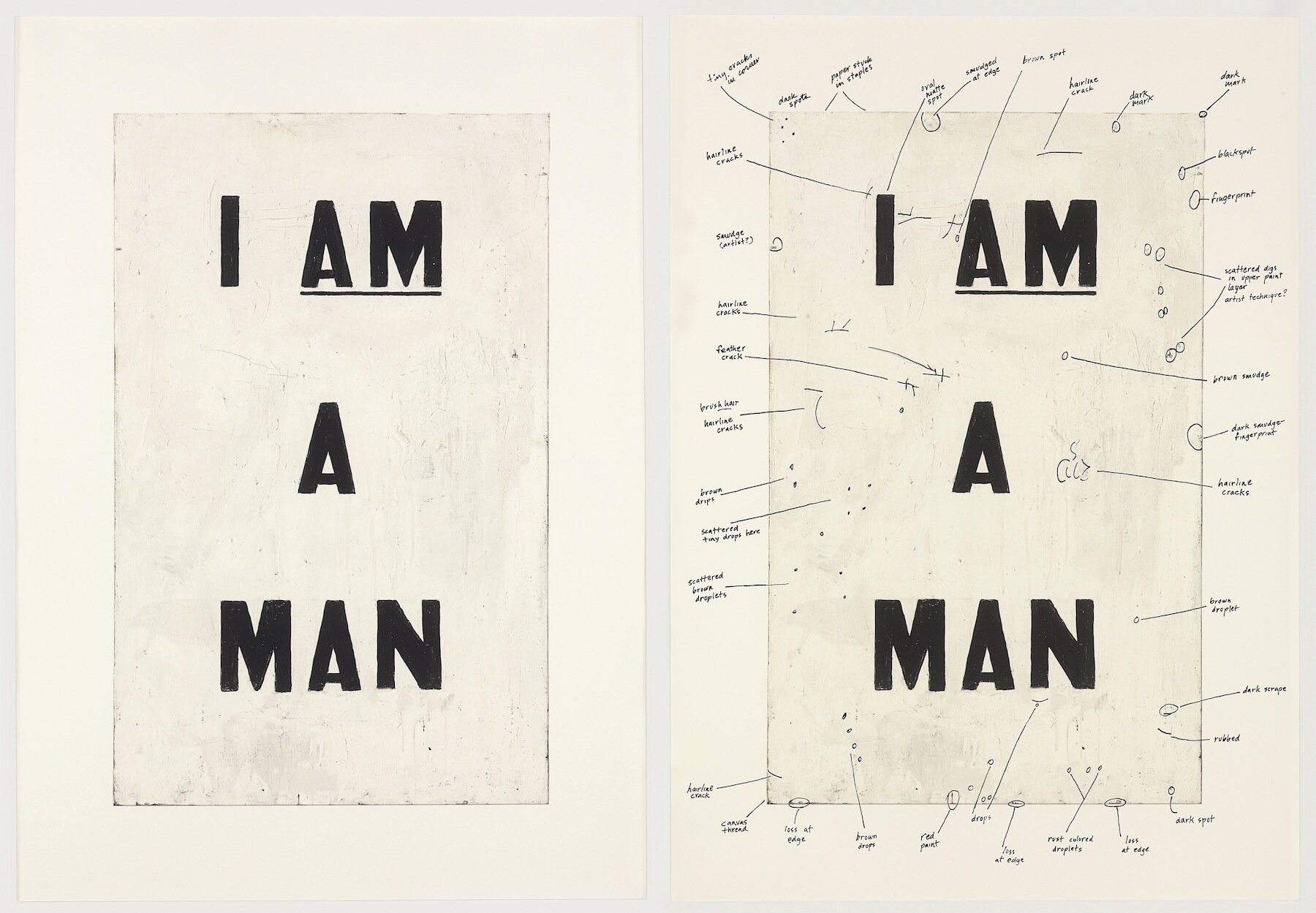

Condition Report, Glenn Ligon (1988)

Glenn Ligon was born in 1960 in the Forest Houses Projects in the south Bronx. Through his work he pursues an incisive exploration of American history, literature, and society across a body of work that builds critically on the legacies of modern painting and more recent conceptual art. He is best known for his text-based paintings, made since the late 1980s, which draw on the writings and speech of diverse figures including Jean Genet, Zora Neale Hurston, Gertrude Stein and Richard Pryor.

“I Am a Man” refers to the iconic posters carried by Memphis, Tennessee sanitation workers during their 1968 strike, which Ligon first saw in congressman Charles Rangel’s office while working as an intern at the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York in the early 1980s. Ligon painted the signs in black, arranged as a diptych. The sibling image is annotated with an art appraiser’s “condition report,” which tracks wear and tear on a piece of art. According to Ligon, “[this] was about detailing not only the physical aging of the painting over time – all the cracks and paint loss and all of that – but also changing ideas about masculinity, changing ideas about the relationship we have to the Civil Rights Movement.”

Ligon's work has been the subject of exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe. He lives and works in New York.

He Was a Man

It wasn’t about no woman,

It wasn’t about no rape,

He wasn’t crazy, and he wasn’t drunk,

An’ it wasn’t no shooting scrape.

He was a man, and they laid him down.

He wasn’t no quarrelsome feller,

And he let other folks alone,

But he took a life, as a man will do,

In a fight to save his own,

He was a man, and they laid him down.

He worked on his little homeplace

Down on the Eastern Shore;

He had his family, and he had his friends,

And he didn’t expect much more,

He was a man, and they laid him down.

He wasn’t nobody’s great man,

He wasn’t nobody’s good,

Was a po’ boy tried to get from life

What happiness he could,

He was a man, and they laid him down

He didn’t abuse Tom Wickley,

Said nothing when the white man curst,

But when Tom grabbed his gun, he pulled his own,

And his bullet got there first,

He was a man, and they laid him down.

Didn’t catch him in no manhunt,

But they took him from a hospital bed,

Stretched on his back in the nigger ward,

With a bullet wound in his head,

He was a man, and they laid him down.

It didn’t come off at midnight

Nor yet at the break of day,

It was in the broad noon daylight,

When they put po’ Will away,

He was a man, and they laid him down.

Didn’t take him to no swampland,

Didn’t take him to no woods,

Didn’t hide themselves, didn’t have no masks,

Didn’t wear no Ku Klux hoods,

He was a man, and they laid him down.

They strung him up on Main Street,

On a tree in the Court House Square,

And people came from miles around

To enjoy a holiday there,

He was a man, and they laid him down.

They hung him and they shot him,

They piled packing cases around,

They burnt up Will’s black body,

‘Cause he shot a white man down.

“He was a man, and we’ll lay him down.”

It wasn’t no solemn business,

Was more like a barbecue,

The crackers yelled when the fire blazed,

And the women and the children too —

“He was a man, and we laid him down.”

The Coroner and the Sheriff

Said: “Death by Hands Unknown.”

The mob broke up by midnight,

“Another uppity Nigger gone —

He was a man, an’ we laid him down.”

He Was a Man by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Concetta Abbate, violin

Cornelius Eady, mountain dulcimer, lead vocal

Robin Messing, vocals

Recorded by Sebastian Sanchez

Mixed by Sebastian Sanchez & Brian Brandt

An Old Woman Remembers

The poem describes the 1906 Atlanta Massacre, in which at least two dozen Black people were murdered by white mobs, including the police and National Guard. In response to the crisis, the Georgia legislature passed a literacy test for voting, effectively disfranchising most blacks.

Her eyes were gentle, her voice was for soft singing

In the stiff-backed pew, or on the porch when evening

Comes slowly over Atlanta. But she remembered.

She said: “After they cleaned out the saloons and the dives

The drunks and the loafers, they thought that they had better

Clean out the rest of us. And it was awful.

They snatched men off of street-cars, beat up women.

Some of our men fought back and killed too. Still

It wasn’t their habit. And then the orders came

For the milishy, and the mob went home,

And dressed up in their soldiers’ uniforms,

And rushed back shooting just as wild as ever.

Some leaders told us to keep faith in the law,

In the governor; some did not keep that faith,

Some never had it; he was white, too and the time

Was near election, and the rebs were mad.

He wasn’t stopping hornets with his head bare.

The white folks at the big houses, some of them

Kept all their servants home under protection

But that was all the trouble they could stand.

And some were put out when their cooks and yard-boys

Were thrown from cars and beaten, and came late or not at all.

And the police they helped the mob, and the milishy

They helped the police. And it got worse and worse.

“They broke into groceries, drugstores, barbershops,

It made no difference whether white or black.

They beat a lame bootblack until he died,

They cut an old man open with jackknives

The newspapers named us black brutes and mad dogs.

So they used a gun butt on the president

Of our seminary where a lot of folks

Had set up praying prayers the whole night through.

And then,” she said, “our folks got sick and tired

Of being chased and beaten and shot down.

All of a sudden, one day, they all got sick and tired

The servants they put down their mops and pans

And brooms and hoes and rakes and coachman whips,

Bad niggers stopped their drinking Dago red,

Good Negroes figured they had prayed enough,

All came back home–they had been too long away–

A lot of visitors had been looking for them.

They sat on their front stoops and in their yards,

Not talking much, but ready; their welcome ready:

Their shotguns oiled and loaded on their knees.

“And then

There wasn’t any riot anymore.”

An Old Woman Remembers by Sterling A. Brown

Read by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

Girl at Gee's Bend, Alabama, Arthur Rothstein (1937)

Stained glass window shards found outside the16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham following the September 15th bombing, Collection of the National Museum of African-American History & Culture (1963)

Shotgun shell found outside the16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham following the September 15th bombing, Collection of the National Museum of African-American History & Culture (1963)

Old Lem

I talked to old Lem

And old Lem said:

“They weigh the cotton

They store the corn

We only good enough

To work the rows;

They run the commissary

They keep the books

We gotta be grateful

For being cheated;

Whippersnapper clerks

Call us out of our name

We got to say mister

To spindling boys

They make our figgers

Turn somersets

We buck in the middle

Say, “Thankyuh, sah.”

They don’t come by ones

They don’t come by twos

But they come by tens.

“They got the judges

They got the lawyers

They got the jury-rolls

They got the law

They don’t come by ones

They got the sheriffs

They got the deputies

They don’t come by twos

They got the shotguns

They got the rope

We git the justice

In the end

And they come by tens.

“They fists stay closed

Their eyes look straight

Our hands stay open

Our eyes must fall

They don’t come by ones

They got the manhood

They got the courage

They don’t come by twos

We got to slink around

Hangtailed hounds.

They burn us when we dogs

They burn us when we men

They come by tens ...

“I had a buddy

Six foot of man

Muscled up perfect

Game to the heart

They don’t come by ones

Outworked and outfought

Any man or two men

They don’t come by twos

He spoke out of turn

At the commissary

They gave him a day

To git out the county

He didn’t take it.

He said ‘Come and get me.’

They came and got him

And they came by tens.

He stayed in the county —

He lays there dead.

They don’t come by ones

They don’t come by twos

But they come by tens.”

Old Lem by Sterling A. Brown

Music by Cornelius Eady

Arrangement by Rough Magic

Emma Alabaster, upright bass

Cornelius Eady, vocal

Leo Ferguson, drums, percussion

Lisa Liu, keyboards

Charlie Rauh, guitar

Recorded & mixed by Jim Bertini

Strong Men

They dragged you from the homeland,

They chained you in coffles,

They huddled you spoon-fashion in filthy hatches,

They sold you to give a few gentlemen ease.

They broke you in like oxen,

They scourged you,

They branded you,

They made your women breeders,

They swelled your numbers with bastards…

They taught you the religion they disgraced.

You sang:

Keep a-inchin’ along

Lak a po’ inch worm…

You sang:

By and Bye

I’m gonna lay down this heaby load…

You sang:

Walk togedder, chillen,

Dontcha git weary…

The strong men keep a-comin’ on

The strong men get stronger.

They point with pride to the roads you built for them,

They ride in comfort over the rails you laid for them.

They put hammers in your hands

And said — Drive so much before sundown.

You sang:

Ain’t no hammah

In dis lan’,

Strikes lak mine, bebby,

Stikes lak mine.

They copped you in their kitchens,

They penned you in their factories,

They gave you the jobs that they were too good for,

They tried to guarantee happiness to themselves

By shunting dirt and misery to you.…

You sang:

Me an’ muh baby gonna shine, shine

Me an’ muh baby gonna shine.

The strong men keep a-comin’ on

The strong men git stronger.…

They bought off some of your leaders

You stumbled, as blind men will.…

They coaxed you, unwontedly soft-voiced.…

You followed a way.

Then laughed as usual.

They heard the laugh and wondered;

Uncomfortable,

Unadmitting a deeper terror.…

The strong men keep a-comin’ on

Gittin’ stronger. . . .

What, from the slums

Where they have hemmed you

What, from the tiny huts

They could not keep from you –

What reaches them

Making them ill at ease, fearful?

Today they shout prohibition at you

“Thou shalt not this.”

“Thou shalt not that.”

“Reserved for whites only”

You laugh.

One thing they cannot prohibit —

The strong men . . . coming on

The strong’ men gittin’ stronger.

Strong men.…

Stronger.…

Strong Men by Sterling A. Brown

Read by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

Ballerinas Kennedy George, 14, and Ava Holloway, 14, in front of the Robert E. Lee monument ahead of its removal following Black Lives Matter protests. Photo by Shane Ford, June (2020)

About the Album Art

Handkerchief owned by Harriet Tubman

Collection of the National Museum of African-American History & Culture

Picking Cotton, Hale Woodruff (1936)

Detail of The Mutiny on the Amistad, Hale Woodruff (1939)

About the Website Homepage Art

Picking Cotton & Mutiny on the Amistad by Hale Woodruff

Born in 1900, Woodruff grew up in Nashville, Tennessee. Woodruff’s earliest public recognition occurred in 1923 when one of his paintings was accepted in the annual Indiana artists’ exhibition. In 1928 he entered a painting in the Harmon Foundation show and won an award of one hundred dollars. He bought a one-way ticket to Paris with the prize money, and managed to eke out four years of study with an additional donation from a patron.

In 1931, Woodruff returned to the United States and began teaching art at Atlanta University. It was Woodruff who was responsible for that department’s frequent designation as the École des Beaux Arts” of the black South in later years. As he excelled as chairman of the art department at Atlanta University, his reputation also grew as one of the most talented African-American artists of the Depression era.

He spent the summer of 1938 studying mural painting with Diego Rivera in Mexico, an experience that greatly affected Woodruff’s evolving style until the early 1940s.

His best-known and most widely acclaimed works at this time were the Amistad murals he painted between 1939 and 1940 in the Savery Library at Talladega College in Alabama. These murals were commissioned in celebration of the one-hundredth anniversary of the mutiny by African slaves aboard the slave ship Amistad in 1849, their subsequent trial in New Haven, Connecticut, and return to West Africa following acquittal.

The curvilinear rhythms of Woodruff’s Mexican muralist-inspired works such as the Amistad murals were absent in his productions of the 1940s.

During the 1940s Woodruff also completed a series of watercolors and block prints dealing with black themes related to the state of Georgia. In the September 21, 1942, issue of Time, Woodruff stated, “We are interested in expressing the South as a field, as a territory, its peculiar run-down landscape, its social and economic problems; the Negro people.”

In 1946 Woodruff moved to New York where he taught in the art department at New York University from 1947 until his retirement in 1968. During the mid-1960s Woodruff and fellow artist Romare Bearden were instrumental in starting the Spiral organization, a collaboration of African-American artists working in New York. Woodruff’s New York works were greatly influenced by abstract expressionism and the painters of the New York School who were active during the late 1940s and 1950s. Among his associates were Adolf Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, and Jackson Pollock. Following a long and distinguished career that took him from Paris to New York via the Deep South, Woodruff died in New York in 1980. (The Smithsonian American Art Museum)